SOMA is an ambitious piece of science fiction inspired by many of the ideas and concepts of Asimov, Bradbury, and Dick. The game actually begins with an opening quote taken from Philip K Dick, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” A sign that the developer Frictional Games is going for something more with SOMA than jump scares and monsters. SOMA wants to talk about identity, humanity, and what it means to be alive, a conceptually frightening counterpoint to physicality associated with its blockbuster sibling, Amnesia: The Dark Descent.

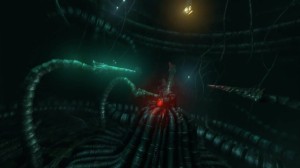

Every great work of horror starts in a similar manner. A simple guy with a simple name like Simon who, through some type of ill luck or coincidence, stumbles unassumingly into a waking nightmare made real. That in a nutshell is SOMA. The story takes place in a giant underwater science facility named Pathos-II where everything that could have gone wrong, did. The experiments have all failed and the machinery and electronics have taken on a life all their own. Circuit boards thrum with electric life and wires spill like intestines out of breached sections of the bulkhead. Simon is forced to flee from lurching robots that leak black blood and cry out to you when you unplug them. Unfortunately I cannot talk about exactly why we are running or what the monsters actually are because that would require massive, game breaking spoilers.

What I can say is that there is a creeping sense of dread that works its way through the underwater world of Pathos-II. It clings to the darkness and always threatens to burst free with every instance of SOMA’s mechanical monstrosities. It is a real shame given that the monsters themselves lack any real palpable malice. Instead they are almost treated as a secondary kind of puzzle. The stealth mechanics lack the depth of Amnesia: The Dark Descent’s and because of this the player is often forced to figure things out through trial and error. There is far less hiding and far more puzzling-out a given threat.

While the overarching fear of death is still very much an issue, the second to second terror bleeds away. I found SOMA’s tight, claustrophobic setting part of the problem. Often times my encounters with creatures were limited to a single room or area. Hiding from them was not a problem and more times than not they simply shambled past with out a second glance. A hallmark of Amnesia’s gameplay was its long wide-open corridors. Stumbling onto a monster was often a panic-inducing nightmare. Hiding was not as simple as passing through a room. I was forced to look for an open door and find a closet or a place dark enough to hide me from the monster’s gaze. SOMA is lacking this in spades.

Most of my time playing SOMA was spent exploring Pathos-II. For long stretches of the game there is very little interaction with other characters or the enemy, it is just the player and the beautiful sound design of SOMA’s world. During one particularly long section of the game I was tasked with traversing the ocean’s floor from one part of the facility to another. While it was fun listening to all the different sounds and taking in the scenery, it is these slow grinding sections of the game that kill all tension and suspense. I kept waiting to be attacked or to catch a glimpse of some hulking threat ahead but was sorely disappointed by the lack of early encounters. In this way the game honestly plays more like a single player adventure. Parts of it really reminded me of Myst, being isolated and surrounded by puzzles and mystery, and less like a traditional survival horror.

None of what I have written so far is to say that SOMA is a bad game, because it most certainly is not. It is a fantastic game, possibly one of my favorites of the year, behind Bloodborne and The Witcher 3. The issue is that SOMA is not really a horror game, not strictly speaking at least. Compared to its pureblooded sibling Amnesia, SOMA is not designed for terror and suspense. Instead Simon is the focus of the story and Pathos-II is the conduit for bigger questions and ideas. The game is less scary and more disturbing at its heart. A large part of this is the sheer amount and quality of the games dialogue. Simon and the other denizens of Pathos-II are alive, or at least they seem to be. And that is what drives the darker currents of SOMA’s storytelling. There was actually one moment in the game where I put down my controller and just sat in the chair thinking about the implications of what had transpired on the screen. Without going into to much detail I can say that SOMA, despite its lack of horror, is overflowing with brilliant and disturbing ideas. Much of the game is spent questioning what it means to be alive. Each enemy and plot point acting as a platform for a slew of frightening possibilities.

The strength and quality of SOMA does not lay in its ability to frighten, you can leave that to Amnesia or Outlast for now, it is in the sheer brilliance of its story and message. I have never seen a game tackle such large and lofty ideas with the success and clarity Frictional Games has achieved with SOMA. What Amnesia: The Dark Descent did in its design with horror, SOMA has done with its examination of what it means to be human, that the lines between human and machine might be quite a bit closer than we think.

The games graphics are equally stunning. From the human machine amalgamation that crawls across the walls and clings to ceilings, to the deep blue currents and ambient life that occupies the dark ocean floor, everything in SOMA looks fantastic and lends a much-needed physicality to the games more abstract concepts and ideas. It is one thing to talk about what it means to be human, but a completely different thing to see exactly what it might look like.

It is this uncomfortable and disturbing combination that drives the story and connects the player to Simon and his quest. We as humans have a certain stake in understanding our relationship to machines. SOMA, like all great science fiction, succeeds because it questions this relationship and the implications of our current trajectory into the future.