Inspiration comes in all shapes and sizes. From bizarre tabloid headlines to snippets of an overheard conversation, anything can contain the elements of a great story. But I think some of the most satisfying writing is when a story comes from something completely ordinary. And as part one of a three-part series dedicated to stories and the writing process, I’m going to show you how to do it. By the end of this article, you will know how to write a short story from the unlikeliest of sources.

For this exercise, we’ll be using the Random Article button on Wikipedia. I’ll walk you through, step by step, noting ideas I think of and toss away, so you can see how easy it is to do yourself. Maybe you’ll get a new method to add to your story skills to get you out of that rut, or have a new exercise when you need a break from your 100,000 word fantasy novel. Either way, I think you’ll love how easy this exercise is to generate all the necessary elements for a great story:

- Build a compelling hook

Create an interesting conflict

Choose characters

Plot story beats

Ready? Let’s give it a whirl!

Step One: Inspiration

Generating a story idea doesn’t always have to come from your imagination. Quite the opposite, as Wikipedia is as perfect a story generation machine as they come. The idea is to be exposed to a bunch of different concepts and things — stuff I may not even know exists. I’ll read the first paragraph or so of each article, just to get an idea what the article is about. If something gets the gears turning, maybe I’ll read a little more. Or maybe not; I’ll see when I get there.

Click.

My first article is about “Fluticasone propionate,” a class of drugs used to treat asthma by affecting a person’s metabolism. Nothing in the first paragraph really sparks my interest, although there could be something interesting in there about hormone-affecting drugs, maybe for a dystopian. But I’m not interested enough, so I move on.

Next we’ve got Aron Thon Arok, a Sudanese politician who helped found a liberation army. Later, he defected to the Sudanese government. It was a short article, so I glanced through the entire thing. As interesting as his life surely was, the article doesn’t have much that grabs me, other than his evocative name. My search continues.

Over the next ten minutes, I scrolled through articles about a rap album, Jetfire the Autobot, a UHF radio station, a consumer goods company, the author of one of those 19th century emigration accounts, a mountain, and an NBA team season. This can happen, and although you can feel like you’re wasting time I urge you to keep going. The articles you do flip through could end up joining together in ways you hadn’t thought of. If you never keep going you might not find it.

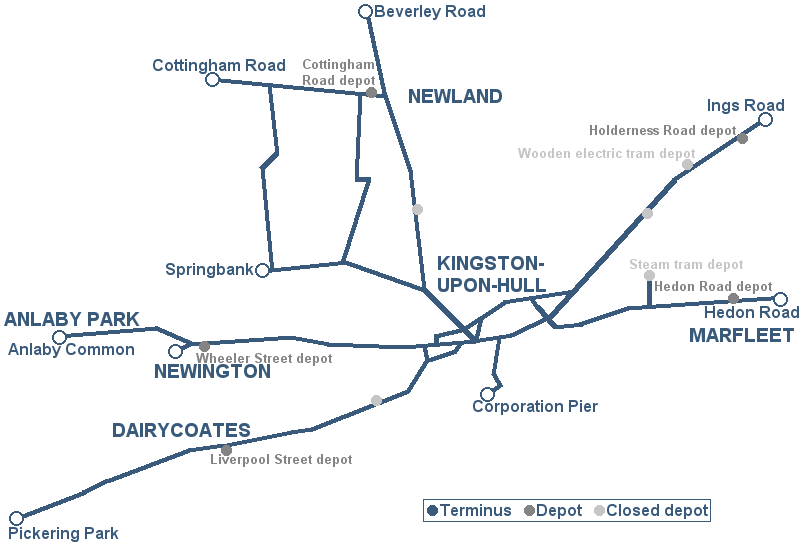

Success! The first idea generator I find is the page on the Trams in Kingston upon Hull, detailing the history of a network of 19th century tram lines in England. The trams were at first horse- and steam-powered, and were eventually replaced by an all-electric system. At this point, my mind starts to see conflict, first a sort of rivalry between the horse and steam tram operators, then the both of them against the new, modern electric operators. I then started thinking about what kind of interesting setting this conflict could be placed in. It could be a historical story, but that would require a buttload of research. The easier route is to make it a fantasy or sci-fi story, inspired by the story kernel I’ve come across but not using it as source material. Like a time period based on 1800s England where horses can change into different forms. I’m interested enough to stop searching and take the next step.

Step Two: Idea Proliferation

To make the idea more story-worthy, I have to seek out more details. I find it helpful to ask questions: What kinds of transportation are the “trams” in my story? Am I going with horses and steam engines? Or some other kind of organic and mechanical beasts? Are these beasts phased out over time, like cars replaced horses in the real world, followed by electric trains? Or did the organic horses somehow evolve to become mechanical? Asking questions helps explore ideas more fully.

My last idea, organic horses that turn into mechanical ones, seems to me the most interesting. It’s something I haven’t come across before, and that combination of the familiar (transportation that changes over time) with the extraordinary (the transportation actually “evolves”) is enough that I’m satisfied asking questions on this particular topic. I could keep going, but there’s no need once I’m excited enough about an idea.

Sometimes the image on the Wikipedia article can spark something. This map for Kingston upon Hull didn’t do much for me, but thankfully its content was, literally, another story. It just goes to show you can never tell what will make your mind start exploding with ideas. However, once we’ve gotten a good initial shotgun blast of ideas, it’s time to put some order to the chaos. It’s time to build a proper story out of it.

Step Three: Structure

Now that I have my premise, I start thinking about what kind of story I want to tell. I usually use Orson Scott Card’s MICE quotient to help structure my story. Choosing to structure my story as a Milieu, Idea, Character, or Event story helps narrow my options and sharpen my focus, so I don’t spend a ton of time building out story elements that won’t be super-relevant.

For this horse story, an Idea story makes sense, as I could make the horses’ evolution process the central focus. I’m not too interested in a Milieu story, since I’m like 90% sure I’m going to go with alternate reality London, which wouldn’t make for too radical a story.

An Event story would be neat too, as I could make the evolution itself the main focus. Say, a handler for one of the horses doesn’t want her beast to evolve, and the story is based on whether the evolution happens or not. Then again, a Character story just sprouted from there, didn’t it? The story could be about the handler wrestling with the evolution of her beast, knowing it’s good for the animal but not wanting it to happen, and how that decision funded tally changes her.

Now it’s time to make a decision. My gut tells me to make it an Event story, which means I won’t have to worry as much about character and I can focus a little more on worldbuilding, which is fun for me. I also think it’d be more challenging to write this as an Event story, and these small exercises are great for pushing your writing skills since they aren’t a big time commitment compared to longer works.

This exercise, combined with the MICE quotient, is a great method for writing short stories around a thousand words long. I try to shoot for that number so I don’t spend too much time on one piece, especially one that I don’t mean to turn into something longer.

Step Four: Outline

So we’ve got a premise and a structure picked out; now it’s time to start figuring out the essentials. At the end of this exercise I want a workable outline with Setting, Plot, and Characters all chosen. This will expedite the actual writing process, as I’ll have some idea of where I want it to go.

Starting with what I know, I’m pretty sure I’ve landed my Setting: 1800s England. We can even use the location from the Wikipedia article — Kingston upon Hull. I can do a bit more research on it later (Wikipedia is great for this as well; just follow the links!), and it might help come up with additional story details. Or I can just as easily change it. But for now, that’s what I’m going with.

I do want to mention the Victorian setting. There’s a natural gravitation to consider a story in this era as steampunk, and I’m going into it consciously knowing that the story will be working a lot of the same themes. However, I don’t want it to be steampunk, and if I can avoid giving it that feel, I will. For me, the creative process is full of making decisions that will affect how I treat a piece. Choosing not to indulge in the steampunk setting means I can treat it with a bit more gravitas than I’m used to reading in the whimsical, almost farcical steampunk stories I’ve read.

As for characters, I’ve already got my conflicted handler. Here’s when I’d usually start figuring out details like sex, background, etc., but I want to lay a little more groundwork before then. Personally, I don’t want more than two characters in a story that I plan on only being a thousand words. Since the audience is only spending a short amount of time with the story, adding more characters runs the risk of confusing readers — or worse, making each character not get their due.

I also want to rule out the horse as a character — we could have a talking horse character, it being alternate reality London, but I’d rather he is just a non-sapient beast. Although I haven’t given much thought to exactly how the horses evolve, the evolution feels to me more like a natural process than some decision on the animal’s part. I’m thinking something along the lines of like the handler has an active process in turning the animal into something more machine, swapping blood for engine oil — that kind of thing.

So since I only have my handler character, I need a foil character. Maybe the handler’s boss who is pressuring her into making the hard decision. He needs motivations too to be well-rounded enough to earn a spot in the story, so I’ll have to consider what he can offer that makes him different from our main. But just knowing he’ll be in the story is enough for now.

Now comes what is always the hardest part for me — Plot. What actually happens in the story. I have what I think is a solid premise, but it desperately needs some action to make it compelling. Without action, it’s just a sinkhole filled with wasted potential.

To do this, I have to figure out what my ending is. The Event story has two outcomes: the impactful, life-changing event is either resolved in a happy way or “everybody dies.” No, not really, but the bad outcome has to leave the world in a worse place than where it was. That doesn’t mean the entire world has to be affected in some end-of-the-world scenario, but it has to have meaning for our main characters. By that note, I start thinking about what effect I want my story to have on the audience. Do I want it to have a happy, triumphant outcome, or a dismal yet thought-provoking one? I usually go for the latter, so let’s try ending on a good note for once.

So my outcome will be that our handler will get to keep her horse the way it is. We can still have this outcome lead to ramifications as well, but we’ll get to those later. Bear in mind that Event stories can still have Character arcs and vice versa; all the stories can have elements of each other bleeding into the others. But the overall structure demands that a certain outcome be paid off. For the Event story, the event in question has to either restore order to our characters’ states or establish a new way of life for them.

Now that I have my outcome, I’m ready to start thinking about characters in more detail now. Our handler, who I’ve already been thinking of as a woman, is already going to be an outsider from her decision to not evolve her horse. I want to salt that wound, so I think I’ll make her come from a rural background while her peers are all engineers skilled in the art of turning horses into machines. She’s a bit ostracized, she doesn’t feel like she relates to the other handlers. Maybe a school setting would be appropriate, or even better, after education. They could be new hires for a tramways company, which is undergoing a difficult transition from organic/steam to electric transportation. It’s the first “real job” these handlers have had, and their backgrounds have had them studying to make the process smoother. (I’m letting the original Wikipedia article influence me a little with this idea here, but that’s okay; ideas are cheap. If I don’t like it, I can always change it.)

So the idea is our handler is outside her comfort zone. She’s used to treating the horses as animals, not simply a means of getting from one place to the next. Her boss, however, hired her on because he saw her talent with the animals, and was hoping she would play along with everyone else when the time came for them to “evolve.” But she didn’t, and now the boss has to confront her. When he gets there, he can’t bring himself to turn her in, and so he does the unthinkable — he lets her leave. Better than that, he provides the means for her to leave, leaving the audience to wonder what his fate will be. But it’s okay, because the immediate conflict will have been resolved.

Keep in mind this is just my initial idea for what could happen, plot-wise. It’s often a good idea to keep thinking up ideas and taking them in different directions. What I should ask is more questions and follow it up with more conflict. For example, let’s ask a series of “yes, but; no, and” questions: Does the handler get to keep her horse? Yes, but it will die if it doesn’t change, so she is effectively killing it. Or no, and she is fired from her job. Asking “yes, but; no, and” questions can help you come up with interesting conflicts across your entire story.

From this, I think it’d be interesting if our main character goes into the situation ready to put a bullet in her horse’s head rather than have him evolve into something she doesn’t believe in. She takes him out to the countryside, where they’ve ridden countless numbers of times, and there she meets her boss. She threatens him with her gun too. I could have the boss talk her down, but I want the handler to be the hero of the story. Whatever happens, she will decide that killing her horse is not the answer, and leaves instead. This is one of those murky outcomes where I don’t quite know what will happen, and it may need to be discovery-written. But I know the direction the story is going; now it’s up to me to get it there.

You’ll notice I don’t have separate sections for Character, Setting, and Plot. That’s because thinking about one of them often informs decisions I’ll make about the others. It creates a more fluid creation process, rather than the “now I’m thinking about Characters” stage and filling in those details before I move onto the next. By attacking everything at once, I can add stuff as needed to my outline.

Step Five: Writing

My biggest issue is knowing when to start the damn thing. I could spend a lot more time world building or doing research, but remember I’m trying to keep this on the short side. To submit this to one of the many great short fiction outlets, staying within a thousand words gives me . A fantasy novel this ain’t; I think I can evoke enough setting details without having to dump more brainpower into figuring out the world. I know the most important stuff — who is in the story, and what happens.

I’m ready to tackle a first draft. During the writing itself is where I’ll discover what kind of tone the story will take, additional character details, and things about the world I didn’t plan for. These kinds of things seem to bubble up from nowhere, but the reality of it is they may be influenced by the stuff I’ve read, both in the article I’ve chosen and the ones before. There’s no guarantee everything will look the way I imagined it for thought out at first, but the only way to know if it’s working is to put fingers to keyboard.

Now that you’ve read how to do this, I urge you to give it a try yourself. Head to Wikipedia and start clicking Random Article and see where it takes you. Or, you can take the “horse evolution” concept and write something from that if you feel inspired. Either way, you now know how to get tons of story ideas from a practically limitless source.

Happy writing

Come back next week to see the first draft of the horse evolution story, complete with notes and annotations from myself and NitWitty’s other editors. And be sure to check out their stories as well!