In today’s games, the freedom to choose good or evil is everywhere. That moral choice can drive gameplay, letting players form their own identities within the games they play. It’s rare these days to get games that support playing one kind of way at the expense of being able to choose the other.

Dungeon Keeper comes from a time when we didn’t have to make tough moral decisions, instead putting us firmly under the black, tattered banner of Evil. Developed by Bullfrog Games in 1997, Dungeon Keeper lets players design devious dungeons to thwart would-be heroes and conquer realms in the name of all that is unholy. It’s a game I’d heard about for years, mostly because of the involvement of game designer Peter Molyneux, the visionary mind behind one of my very favorite games, Black & White. I knew little else about Dungeon Keeper, other than it sounded like the perfect game to get Retrograded for this month’s celebration of villainy.

So don your deepest hood and curliest mustache and take a walk with me, for where we’re going, only darkness reigns supreme…

A Devious Concept

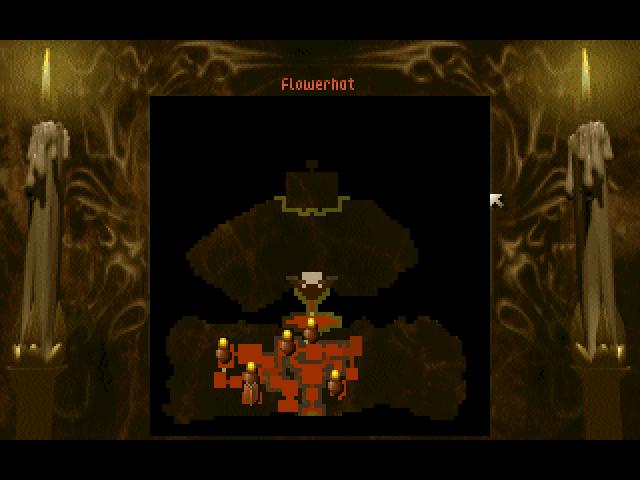

Dungeon Keeper turns the typical fantasy strategy genre on its head. Instead of controlling heroic knights and archers to vanquish a dungeon’s demonic denizens, you’re raising a hellish force of imps, beetles, and other nasty critters to oust do-gooders from the realm. The game is divided into stages, each of which is introduced by a devilishly wry narrator. The level select screen shows a map of an idyllic fantasy land, with peaceful towns and hamlets nestled into its rolling green hills. Below, however, is where the real action happens.

You start with a handful of imp workers who mine gold and carve tunnels and rooms into the rock. They also have the important task of claiming land for you; with them, you build the all-important areas you need for a fully operational dungeon.

My early impressions were pretty positive. Running on DOSbox (a Retrograded staple, it seems), Dungeon Keeper looked a little muddy. How these old games look has little bearing on my enjoyment, but I’ll admit the earthy underground palette of brown, brown, and more brown didn’t do Dungeon Keeper many favors in the eye candy department. Sound design is another story, as the skittering of my minions carrying out my will filled me with delight, aided by an ambient music score that heavily reminded me of Diablo II’s Den of Evil.

Tutorials rolled out slowly yet evenly; I didn’t feel overwhelmed at the beginning like I had in other old games. Instead, I was tasked with expanding my evil influence, starting with the gold mines to stock up my treasure rooms, and ending with the Portal which would supply me with monsters. Over several stages, I was introduced to new features that I could add for a bigger, more terrible dungeon. My power grew steadily.

SinCity

If you strip away all the dry humor and flipped fantasy tropes, Dungeon Keeper is a sim builder at its core. You arrange and place zones that have different functions, and if you do it right you’ll win each level. There are lairs for housing your monsters, and training rooms for them to level up in; treasure rooms to hoard your gold; and workshops to research traps and doors — and likely many, many other kinds of zones. I only unlocked up to the workshop, but I’m sure these dungeons could get pretty complex.

The goal of each level I played was the same — build out the dungeon until the good guys arrive, defeat the lord of the realm, then do it all over again. I didn’t mind having to rebuild every level; unlike a persistent city game like SimCity, Dungeon Keeper is more objectives-based like a proper RTS. Its structure totally supported my playstyle in these games, which is to build a giant force over a long period of time, then crush the opposition in one blow. It’s a crappy playstyle from a competitive standpoint, but it works just fine for single-player games like these. But it meant I could take my time and learn the game’s systems at my leisure.

The more I played the game, the more comparisons I drew to Black & White. I could pick up imps and other monsters to place them where I wanted. I could even slap my imps to make them work faster, a feature that reminded me of the times I had to discipline my creature. I never saw much need to (the first few levels weren’t very demanding), but the fact that I could abuse my minions did make me feel like I was a properly evil taskmaster.

This evil delight extended to my other actions. The first time I defeated an enemy Lord with a swarm of beetles, I felt a cruel sense of satisfaction. And when I moved onto the next stage, the level select screen showed the realm I conquered as a blackened, blasted land. That kind of outward appearance is a great reward for choosing to play evilly.

The (Inter)Face of Evil

There aren’t a lot of menus in Dungeon Keeper. There are tabs that tell you the kinds of rooms you can build, the spells you can cast, and the projects from the workshop you can install. Among the most helpful is the monster menu, which shows how many of a kind of monster you have, what they’re doing, and if they’re in combat. What’s great is that you can pick them up from this menu as well, in multiples to boot, and then drop them where the fighting’s thickest. The real bummer is that these menus don’t tell you much information. Hovering over a lair or hatchery selection doesn’t remind you what they’re for, an issue when you’re playing over multiple play sessions as I was. For example, it was easy to assume I needed lairs for my monsters, but when a stage required me to keep my fly lairs separate from my spider lairs, I experienced several frustrating minutes before realizing I needed to physically pick the critters up and move them away from each other. Not the most intuitive thing.

Even worse than the menus is the map. Your dungeon is marked in red, and you can zoom in and out. But the map only shows you where you force is; it doesn’t tell you which rooms are which. The only way to tell your hatcheries from your training rooms is to select that option from the menu, which then flashes on the map in an epileptic fashion. Other strategy games like Warcraft and Starcraft highlight your areas in similar fashion, but that’s so you can tell your town apart from the rest of the map. Dungeon Keeper’s map is occupied by dank, dark earth — you could easily tell what part of the map is yours if you were given a rainbow of colors to identify your dungeon’s different rooms. Then again, maybe more colors would undermine your evil intentions. That’s the kind of design philosophy this game subscribes to.

Although Dungeon Keeper added new features and concepts gradually, letting me create bigger, more complex dungeons, I never got a good sense of whether I was doing anything right. I had plenty of notice whenever I was doing something wrong, as indicated by multiple text and audio-based warnings. The repeated booming of “YOU NEED A BIGGER TREASURE ROOM” and “YOU HAVE CREATURES THAT CANNOT GET TO THEIR LAIRS” reminded me of Black & White, Molyneux’s other masterpiece. Like the needs of my insufferable peasants in that other game, the demands of my minions drove the infrastructure of my town — or in this case, my dungeon. The information was handy to know, but in Dungeon Keeper I never really knew what to do about it. In one level where the reminders were getting particularly rambunctious, I expanded lair after lair and hatchery after hatchery, trying to appease my minions to keep them on my side. But once the warnings stopped, I never felt satisfied; the game never reinforced my behavior as positive. I don’t think myself a needy gamer, but there should be something to show for playing by a game’s rules, no? In Black & White, building the requested creches and other civic buildings has a direct result on gameplay — more children to sacrifice or grow into proper worshipping adults.

Maybe this has to do with the freeform nature of not only the placement of your buildings but the sizes and shapes of them as well. The game recommends building rooms of at least 9 spaces for maximum efficiency. But what about Bile Demons, who the game state needs bigger rooms? How big is too big? These questions were never really answered in several hours with the game.

Ultimately, I appreciated the ability to design my dungeon to my liking. I built long, winding corridors with monster-filled lairs to ambush enemies, and hatcheries outside every training room to provide energy boosts for my most dedicated iron-pumping beasties. Once doors and traps were introduced, I cackled in delight more than once at the prospect of my treasure-seeking enemies entering a room, only to find it was filled with nothing but poison gas traps. For my creative side, Dungeon Keeper wins because it let me build the way I wanted; for my gamer side, it succeeds because it presented enough options to let me figure out devastating combos.

One final gripe, and one that has less to do with Dungeon Keeper and more to do with the platform, DOSbox. On several occasions my mouse would get stuck on the far left of the screen, scrolling the map all the way to the very end of the stage — a considerable distance. I had to delve into the help forums to solve it (swiping the mouse in the direction it was stuck in seemed to work).

Building a Better (or Worse) Tomorrow

Despite my problems with it, Dungeon Keeper is my kind of game. It supports my strategy game playstyle (flawed as it is), and I found myself intrigued by its sense of progression, which left me wanting to know what diabolical contraption I would unlock next. Although I never got far enough to truly create the death-dealing dungeon of my darkest dreams, I’m confident that further playing would yield something that would resemble that.

The idea of building your own dungeon to fend off do-gooding adventurers who are after your hard-earned treasure — that’s the sinfully sweet icing on this Devil’s food cake. But that aesthetic wouldn’t amount to much if I didn’t find the systems half as engaging as I did. A concept alone doesn’t make a game fun; it helps, but it’s not what’s going to pique my interest for hours on end. And the act of designating zones, claiming land, building on the land, and then expanding is the kind of satisfying loop I look for in any strategy building game.

Dungeon Keeper is a bit rough around the edges, but that’s expected for Retrograded. It’s rare that a game this old (19 years isn’t that old) can grab me purely from a gameplay standpoint. Dungeon Keeper wasn’t tied to big franchises like Warcraft or even XCOM; its systems was all it had going for it. And as it turns out, the idea of returning to those systems is more than enough to have me gleefully rubbing my hands together, anticipating my next evil plan.

Retrograde: A Villainous Victory