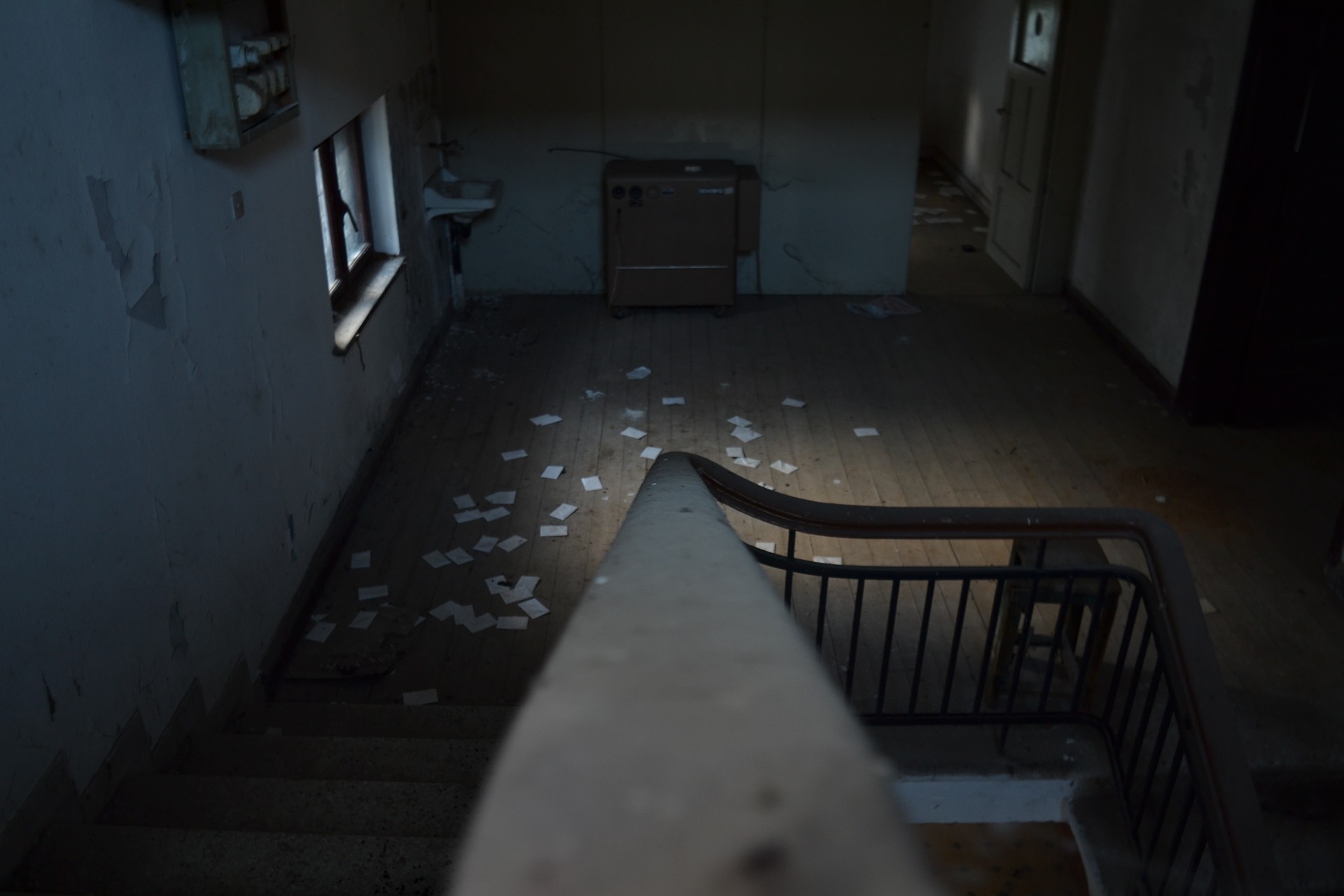

Things are getting spooky here at NitWitty, and Prose Dive is joining the fun. While there’s no shortage of speculative pieces to turn our discussive outputs toward, I thought I’d stay on theme with the rest of our ‘zine and choose a short story with a darker tone.

“Ten Things to Know About the Ten Questions” by Gwendolyn Kiste, published in Nightmare Magazine, shows us a world plagued by sudden, widespread disappearances that are as problematic as the alienating methods being used to try and prevent them. This is not a horror story in the traditional sense. The horrifying parts are in how the story relates to our own world. Drawing influence from real world occurrences, the story points out how we deal in times of crisis – and how that may end up hurting more than helping.

The Plot

Vivienne is in sixth grade when the disappearances start. No one, including her parents, thinks anything of them at first. But then the disappearances start increasing, and so do certain initiatives to spread awareness of them. Public service announcement posters start going up, students are placed in special classrooms – there’s even a hotline to call. Paranoia begins to spread as people tell on their neighbors under the pretense that they are helping their fellow man. Eventually, things get so desperate that to be in danger of disappearing is seen as an ailment, something many people are ostracized for. “Deviants” is the word used. Homes that were once lived in by those who have gone will not get sold. Treatment facilities are instituted to provide an even more permanent place of separation than the classrooms.

Vivienne’s world becomes consumed by the Ten Questions, more a series of statements, really, that are distributed regularly to identify who is “at risk” of disappearing. Vivienne takes the test as a child and scores so low she is placed in a special classroom, a dismal place kept separate from other students. But it is there that she meets Tally. As the world around them either disappears or alienates them for being different, the two girls develop a strong bond, and their friendship seems like the only thing that will endure the crisis.

The ending is predictable, even inevitable – Tally disappears – but much like Vivienne and Tally’s friendship, getting to the end point brings the story together.

The Setting

The supernatural nature of the disappearances is backdropped by speculative realism. The speculative parts of this story are in its “what if?” questions, as in, “What if the fear of vanishing was directed not at the phenomenon itself but toward the people doing the disappearing?” The invention of the Ten Questions are a system very much in the vein of “for your own good,” a kind of Big Brother for the modern age. People are disappearing and yet there is a need for Them (it isn’t clear who “They” are, but my money’s on the government) to issue a form of control to stop it from happening. The regular issuing of the Ten Questions is for the Average Joe to grasp onto and let them gain some semblance of normalcy during the crisis.

Only this story isn’t about that. The machinations of an ill-meaning government are outside the scope of Vivienne’s view. She’s very much focused on her little slice of the world, which includes her family, her school, and Tally. The signs that the world is falling apart are all there, but they serve as a nice backdrop. Like truly well-written prose, we can imagine it without it really having to be said. The real fun comes from speculating on the set pieces that are actually present.

To me, the disappearances aren’t the scariest part about this story. I mean, people randomly vanishing is scary, but I’m more frightened by the level of imposed control and everyone’s willingness to create an Other. You’ve seen, maybe even heard, those PSAs at the transit station: “If you see something, say something.” They’re a warning and a call to action all in one, meant to empower the individual to take the initiative and report any wrongdoing. The Ten Questions are like that, helping to (supposedly) identify people who are at risk of disappearing before they get a chance to. This passive solution is scary, scarier even than a more forceful policy. We could have gotten a story about a girl who fails the Ten Questions, is taken to a government facility, and is subjected to more rigorous testing to determine the meaning behind the crisis. That option certainly seems the more Hollywood outcome, but it’s more slasher flick versus psychological horror. It’s tense, but not necessarily frightening. In my opinion, seeing blood and guts spill is scary, but what’s under the killer’s mask is even more so; I find the implementation and widespread acceptance of the Ten Questions the part that makes my flesh crawl.

The Characters

We’re dealing with a crisis on a global scale, yet author Kiste manages to zero in on just a few characters. Short fiction usually gravitates toward a small character roster, but in “Ten Questions” I feel the relationship between Vivienne and Tally is especially important. The deep friendship they develop isn’t just an excuse to get more characters in the story, it’s a direct result of the program that singled them out. In a way, their relationship is in defiance of the Ten Questions system and the public shunning that resulted.

Characters defying the system – what a concept! Seriously, though. I think it really works for this story because of what the characters symbolize. Tally is already on that level when we first meet her; she plays her “deviant” role well, first as a classroom delinquent too smart for her own good and later as an obstinate young woman who doesn’t give a damn what society expects from her. Vivienne becomes her star pupil, motivated only by the desire to be nearer to her friend in a time where the world is literally fading away. Despite the circumstances, they’re normal kids; civil disobedience works for them.

And Tally’s motivations? They aren’t quite clear, and they don’t need to be; she isn’t the one who grows as a character. Tally needs to serve as the catalyst for change, and she succeeds by the story’s end – her disappearance marks the end of special programs across the nation. The disappearances don’t stop, but the alienating, at least on a governmental basis, ends. So although Tally is the more dynamic character of the two girls, Vivienne is the one who changes.

Through Vivienne’s eyes, we see disappearing as something to be fearful of because it would mean leaving behind the one who matters to her most.

Author Kiste built a scenario that shows the fear of being alone simply by showing us a friendship too touching to let go. You might find the Ten Questions and its program the scarier part of the story, but remember – it’s only scary because of what it would take away from the characters.

The Takeaway

There are two ways of looking at this story: how people react to a crisis, and how a person reacts to it. I can’t help but be reminded of that line from Men in Black where Tommy Lee Jones’s character is talking about mob mentality. “A person is smart,” he tells Will Smith. “People are dumb, panicky, dangerous animals and you know it.” We don’t get to see much of this dangerous dumbness exhibited in “Ten Questions,” but we do get a fair bit of how our society might handle something on this scale. We didn’t get details on what Science (yes, the capital ‘S’ kind) was doing to look into the disappearances, and maybe that just wasn’t on Vivienne’s radar. But the entire initiative behind the Ten Questions themselves seems very modern to me, a solution thought up by mass media manipulators giving people too much credit as rational human beings.

There’s a message about the Other in the story too. It’s quiet, but it’s there. People who are at risk of disappearing are cut off from others, and the ones who are next, according to the Ten Questions, find comfort in each other. But Tally and Vivienne don’t rise up against the ones who’ve wronged them; they go through their lives in the crazy, crazy world they live in until their friendship expires. And that to me is one of the scariest things there is.