Mangaka Masterwork: Real

In today’s world of technology, we as a society have begun to standardize stories and fiction. We are more inclined to accessibility and ease rather than taking the time to nurture an experience capable of only existing in the slipstream between words and the page. Formulaic writing and expressions populate reality and the wonderful world of characterization fades into the background. In contrast manga occupy a unique position in the literary world. Hand drawn art and the weekly/monthly cycles in which they are published offer the creators an opportunity to take risks and tell stories with real emotional depth. One chapter at a time they are able to build worlds and characters that defy standards and delve into the gritty underground that is the human psyche. Drawn art is unique only to the comic medium, a narrative can take shape as we trace intricate combinations of hatch-marks and line work. Bold shadowing done with a fountain pen stretches deep into the page and what is born is an experience formed from more than our eyes, but also from a combination of the senses and imagination.

The strength of such an art-fueled form of storytelling is in its ability to take that moment and to transport and transform it. To take us from businessmen, cooks, accountants, scientists, and turn us into something else entirely.

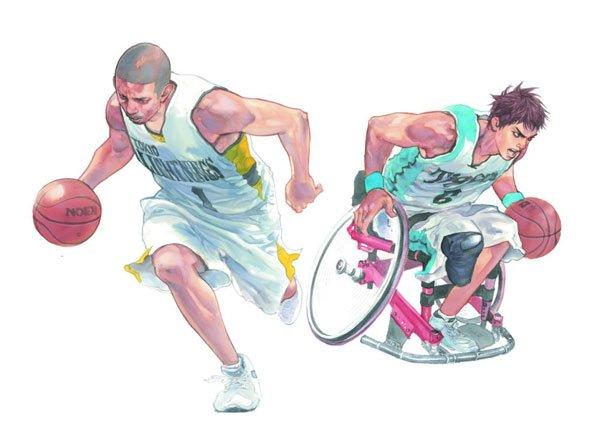

In Real Takehiko Inoue takes full advantage of this by plunging us into the minds of the physically and emotionally disabled. In this story we are not warriors with near superhuman strength, we are broken and trying to find our place in a world that often moves on without us. Real is a story about wheelchair basketball, paralysis, and facing the fragile truth that our bodies are far from invincible. Our worth is not in our physical facilities but in our ability as human beings to overcome adversity and balance the tilted scales Lady Fate has seen fit to deal us.

Fighting the Tides of Fate

The very first character Inoue introduces to us is Tomomi Nomiya, a passionate delinquent and basketball player who is involved in a motorcycle accident that paralyzes his female passenger. Due to his often over the top and criminal behavior ( in one scene he says good bye to his former high school by pinching off a loaf next to the front gate,) he is blamed for her condition and driven into depression. Nomiya is not just a vehicle for the plot or a message or an idea. A hallmark of Inoue’s style of art is his ability to sketch faces and emotion. You can see the guilt and regret heavy in the lines on his face and in his eyes. Nomiya is devastated by the long-term implications of his accident, and hairline cracks have begun to spread across his unwavering self-confidence. As a reader we are faced with the difficulty of his situation. What should he do to help the girl whose life he has changed forever. His answer is to visit her often and walk her around the health facility. Which is where he meets Kiyoharu Togawa the second protagonist, an amateur wheelchair basketball player who is shooting hoops at an on site indoor gymnasium.

Kiyoharu Togawa is a fierce, unyielding teen who lost a leg in his battle with bone cancer. His personality, unlike Nomiya, is directly at odds with our expectations and his own physical disability. Togawa is drawn with sharp, strong lines that accentuate a muscular face framed by thick stubborn eyebrows. It is quite obvious from the onset that he could give a shit about his disability. In fact, the first interaction that occurs between our characters is a fight via basketball. One which Togawa wins with his prowess on the court, a talent unhindered by he limitations of his body. By introducing such a character, Inoue is giving us a front and center view of what its like to live disabled. Namely that in some cases, it doesn’t matter. The injury or deformity does not define who a person is, or what they are capable of accomplishing. In many cases this is determined by outlook and expectations. A opinion he makes brutally clear with our third and final protagonist, Hisanobu Takahashi.

Takahashi is an arrogant, self indulgent, teenage basketball star whom karma catches up with. At the behest of a girl he steals a bike, and while running away is stuck by a car. In one stupid split second decision he loses everything as his spinal cord suffers serious injury and he forever forfeits his ability to walk. Takahashi’s character evolves under the gruesome realities and pen strokes Inoue draws out for him. In the beginning his character is drawn with the strong clean lines of a healthy athlete, while afterwords his character’s appearance is almost sketch-like in its haggard display. Through Takahashi we are immersed in the transformation from able-bodied athlete to severely crippled patient. A mutation that is explored in all of it’s gritty, heartbreaking glory.

The Glory of Manga

Real does not pull punches. Quite the opposite, it the undisputed heavyweight champion of despair, and it wants to beat the living shit out of its lightweight reader base.

Takehiko Inoue takes a real risk by animating his story in the ugly underworld of physical disability. His narrative and art does more than just depict these young men, it immerses us in their struggle. It shines light on a perspective that is very rarely seen or ever talked about, that is, how the world treats and views those living in the world of disability. Real is frustrating, embarrassing, hilarious, and heartbreaking, it’s a story that scales the social boundaries that surround discussions on the handicapped.

Takahashi, Nomiya, and Togawa, are all characters who’s stories explore the extremes of the human condition. And It is for this reason that I chose to follow Miura’s Berserk with Inoue’s Real, because much like Guts the three protagonists are fighting tooth and nail against a fate that threatens to define them. Whether its Nomiya as a screw up, Togawa as fool fighting an inevitability, or Takahashi grappling with the realities of his handicap, all three character’s face definition. The outcome of these personal battles, you will have to read for yourself.