There are few things as scary for a creative type than staring at a blank page. If you make stuff for a living, your hand poised at the top of the page presiding over miles of white space is probably one of the worst feelings in the world. It doesn’t matter if that page is for writing, for for building a game, or for making art. Boundless bits of whatever, is a fundamentally worrisome proposition.

Well, there is another feeling that is even more terrifying; imagine for a second that you’ve made a game before. Pretend that what you made was interesting, groundbreaking, and a critical darling, was played by millions of people and is often on the list for greatest games ever made. Now imagine that you are tasked with capturing lightning in a bottle again. Welcome to Hell.

Some creators don’t even try. While publishers or studios would really like them to get deeply involved with working on The Sequel: The Search for More Money, sometimes the creators just go completely off the rails. They look at what was done before and instead decide to creatively walk out there and out there in the wilderness, where thar be dragons. Well, also in the wilderness there might be concepts and ideas that occasionally are revolutionary in hindsight. That’s because, if you have to do it again, you might as well go for broke.

In 1985, Nintendo released the delightful Super Mario Bros for the Nintendo Entertainment System. At the time it was easily one of the best things on the platform, and a follow up was commissioned. So the development team, led by series creator Shigueru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka,the Assistant Director for SMB, began to create a follow up for release in the next year. The outcome was the weirdly painful Super Mario Bros 2. For those of you in the US, this game is better known as “The Lost Levels.”

The game is, well, let’s be polite and call it an abomination. Super Mario Bros 2 (which I will call The Lost Levels moving forwards for clarity) takes everything about the original SMB that made it special and threw it all away. For example, while SMB goes out of its way to make you feel safe, the first mushroom you encounter in The Lost Levels is a Poison Mushroom that damages you. Why does it do that? Fuck you, that’s why. This game was designed to be hard as a “Challenge” according to the developers, but for people that hadn’t mastered SMB, it was unplayable.

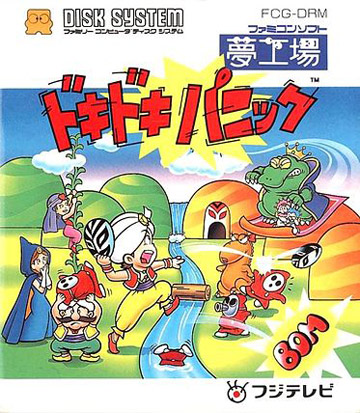

Coincidentally, when offered the game for local publishing, Nintendo of America said, “Nope.” They still needed a game to put out for Xmas and Mario was kind of the mascot for their nascent system. The solution was to release a different game that Miyamoto had been working on called Doki Doki Panic!

Of course this didn’t actually fix the whole problem with needing a Mario game for Xmas 1986. Lil’ kids were going to cry and grandmas were going to have cookies hucked at them if Mario didn’t show up with Santa. So Nintendo did what they could do: they released Doki Doki Panic! and reskinned it instead.

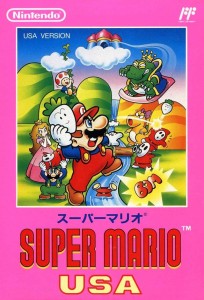

This version of the game is what was released in the US a Super Mario Bros 2. What you see above is proof that Nintendo will not let a good thing go to waste, so they released Doki Doki Panic! again and called it Super Mario USA. You just know that some poor bastard somewhere got both games for their birthday, and now has a drinking problem.

So for many people the followup to Super Mario Bros was really strange. It was full of vegetables, while goombas and koopa troopas and Bowser were nowhere to be seen. When you jumped on a dude, instead of sending them into the great digital hereafter it did less than nothing. For veterans of SMB, Super Mario Bros 2 was some sort of weird acid trip.

The thing is that SMB2 became really influential in the long run for the series. In SMB the characters were the same in terms of play characteristics. The Lost Levels made an attempt to differentiate the Mario Brothers, but SMB2 made the differences explicit and matter to the gameplay. Mario, for his part, plays almost exactly as he does in SMB. If nothing else, he feels correct. Luigi has this weird floating jump with a strange, high arc, and is shown as having different physical characteristics in game form.

What’s more, SMB2 made characters out of Princess Peach and Toad. In SMB they were window dressing at best. Toad was just the guy everybody hated because all he did was share bad news with you. The Princess was in another castle. In SMB2 they were made playable characters – a trait that they would carry on in later games of the series. Not to mention that SMB2 introduced the backup enemies of Birdo and Shy Guys to the Mushroom Kingdom.

Basically, the weird sequel to one of the most beloved NES games began to fill out the entire world. SMB2 is why the series has had the longevity that it has. Super Mario had the gameplay, but was very straightforward. SMB2 began the process of filling out the map, and the world that it began to hint at is one that we’re still exploring almost 20 years later. That’s not bad for a last minute reskin.

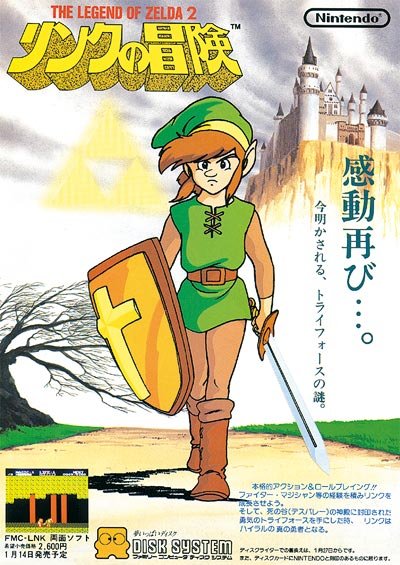

While Super Mario 2 from a story perspective is a side story, our next example of a radically strange sequel is a direct continuation of the first. I’m talking about Zelda 2: The Adventure of Link. Developed in 1986 as a follow up to the critical darling The Legend of Zelda it was produced by Miyamoto (because that dude is everywhere), after directing the first in the series.

The gameplay in The Adventure of Link is radically different than in The Legend of Zelda. While LoZ was a top down adventure game, AoL had all of the combat presented as a side scrolling action game. This turned much of the focus for combat towards effective use of the shield and using jumps defensively. It was a radical departure to be sure. In addition, the game introduced a high/low blocking system for enemies, making it so that choosing the correct method of attack was the key to defeating them.

This was exacerbated by the fact that, unlike in LoZ, the items you picked up did very little in the actual game and were not used in combat. There are no boomerangs, arrows, bombs, or anything of the sort. The combat in AoL was designed to be about the interplay of sword and shield. That’s it. If you don’t like it, deal with it.

It wasn’t just the weapons either. Items that seemed like Zelda stalwarts such as hearts, fairies, and the ubiquitous rupees were nowhere to be seen. Instead they were replaced by jars of magic. Not to mention that having full life gave you the saddest thrown sword ever.

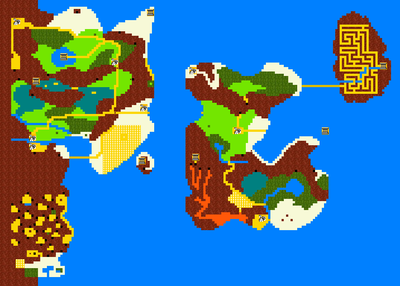

Generally speaking, AoL was seen as a major letdown, and is considered to be the black sheep of the series. Only, much like Super Mario Bros 2, it actually has a lot of pieces that got carried forwards. Let’s start with how the world is created. In LoZ the world map is large, vast, and devoid of people that aren’t Link or the titular Zelda. AoL introduces cities and NPCs and makes Hyrule seem far less artificial. Don’t get me wrong, the world map of LoZ is awesome and I want it on a quilt, but the world of AoL looks like a place that people would exist in. That makes it interesting in and of itself. If you want proof of it just look at every Zelda game to come out since. They all have towns, some may not have very many, but they all have towns. That system of world building started with AoL.

The other thing about AoL is that while it became this weird, “other” in terms of the top down Zelda games, it more or less set the template for the 3D ones. To wit, in Ocarina of Time, while you can get more weapons and you can use them in combat, they are tools designed for special tasks. The core of the gameplay in OoT is the interplay between sword and shield, much like in AoL. Furthermore, concepts such as movement as a means of defense and timing based attacking in the 3D Zelda games became the default methods of interacting with enemies.

Consider the Z-Trigger from Ocarina of Time. That was a way in OoT to lock onto a specific enemy so that you could fight them without losing track. A lock on function became one of the defining traits, not just of OoT but of 3D action games in general. The impetus for creating it though, is because the designers wanted a system of combat that used the shield and allowed a specific freedom of movement. In other words, in making the transition to 3D, they weren’t looking at LoZ or the more recent A Link to the Past; instead they started pulling combat tricks directly from AoL.

Like Super Mario Bros 2, the Adventure of Link was considered at the time to be a noble failure. Instead in not doing what their predecessors did, they were able to expand the ideas of the franchise into directions that the creators never would have found if they had made sequels that just slavishly did what had been done before. So if you find yourself staring at that blinking cursor and trying to figure out what you are supposed to be doing, the answer is simple – do what you want. Maybe, just maybe, there’s something strange and new out in those uncharted waters – beyond all of that white space. It worked for Link and Mario after all.